In this episode of Meaningful Work Matters, Dr. Alan Waterman joins Andrew Soren to unpack what eudaimonia looks like in everyday life, especially when it comes to the work we do.

Dr. Waterman is Professor Emeritus of Psychology at The College of New Jersey. He is widely recognized for his pioneering research on identity, intrinsic motivation, and the distinction between eudaimonic and hedonic well-being. His work brings together philosophy and psychology to explore what it means to live a life of purpose and fulfillment.

Their conversation touches on themes like motivation, personal values, calling versus obligation, and the kind of support individuals need to develop a fulfilling life, whether that fulfillment is found through their job, outside of it, or both.

From Aristotle to Identity: What Is Eudaimonia?

Dr. Waterman explains eudaimonia as the process of realizing our fullest potential.

He draws an important distinction between two kinds of potential. Species-generic potential refers to the abilities and traits that are uniquely human, such as reason, creativity, and moral reflection. Individual-specific potential is about the strengths, values, and capacities that are unique to each person.

Both types matter.

From Waterman’s perspective, fulfillment happens when we develop our own individual strengths within the broader context of what it means to be human. It is not just about performing well, but about growing into the kind of person we are most capable of becoming.

He describes it this way, inspired by the work and research of David Norton:

“Being where one wants to be, doing what one wants to do, where what you are doing is something that is worth doing and worth doing to the best of your ability.”

This definition highlights that living well requires both self-knowledge and effort. We need to know what we are capable of and choose to act on it.

For Waterman, this is what gives life its meaning.

Work as a Calling vs. Work as a Job

One of the clearest applications of eudaimonia to modern life is how we approach work. Waterman distinguishes between work as a calling and work as a job.

Work as a calling is intrinsically motivating. It’s often tied to activities or roles to which people feel connected. Not because of pay, status, or convenience, but because they find them worthwhile.

Work as a job, by contrast, is usually chosen for practical reasons and tends to be extrinsically motivated. It may be necessary or even enjoyable, but lacks the deeper sense of purpose that defines a calling.

Waterman challenges the notion that callings are rare.

In his view, many people experience a calling: teachers, scientists, first responders, artists, etc. However, they may not always label it as such. He also emphasizes that callings can evolve over time and show up in multiple domains of life, not just in paid employment.

Intrinsic Motivation and Person-Activity Fit

So how do we know what path might lead to fulfillment?

Waterman points to intrinsic motivation as a key signal. The activities, values, or beliefs we feel a natural pull toward are often the ones most aligned with our individual potential.

He encourages us to pay attention to resonance, a term borrowed from music. Just as certain notes create harmony within us, certain tasks, roles, or values feel more aligned with who we are. When we ignore those signals, we may succeed externally but feel disconnected internally.

Waterman also highlights the difference between interpersonal comparisons (how we stack up against others) and intrapersonal comparisons (what we do best among all our own options).

Eudaimonic fulfillment, he argues, comes from the latter.

“We are not here to fulfill someone else’s version of success. The work of a meaningful life is identifying and developing the strengths that resonate most for us.”

Harmonious vs. Obsessive Passion

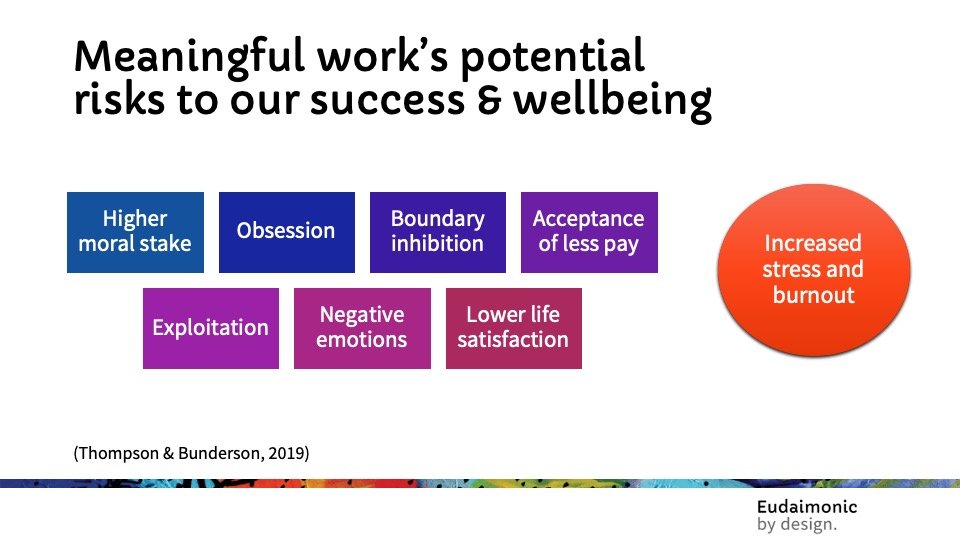

The conversation also explores a critical distinction in motivation theory: harmonious passion versus obsessive passion.

Harmonious passions are intrinsically motivated and additive. They support our overall well-being and integrate well with other areas of life.

Obsessive passions on the other hand often involve a rigid attachment to goals or identities. They can lead to burnout, alienation, or the neglect of other important life domains.

Waterman encourages anyone stuck in an obsessive loop to step back and assess what’s working and what’s not. He suggests revisiting earlier moments in life where balance or joy were more present. Oftentimes, rediscovering meaning starts with exposure to something new.

What This Means for Managers and Workplaces

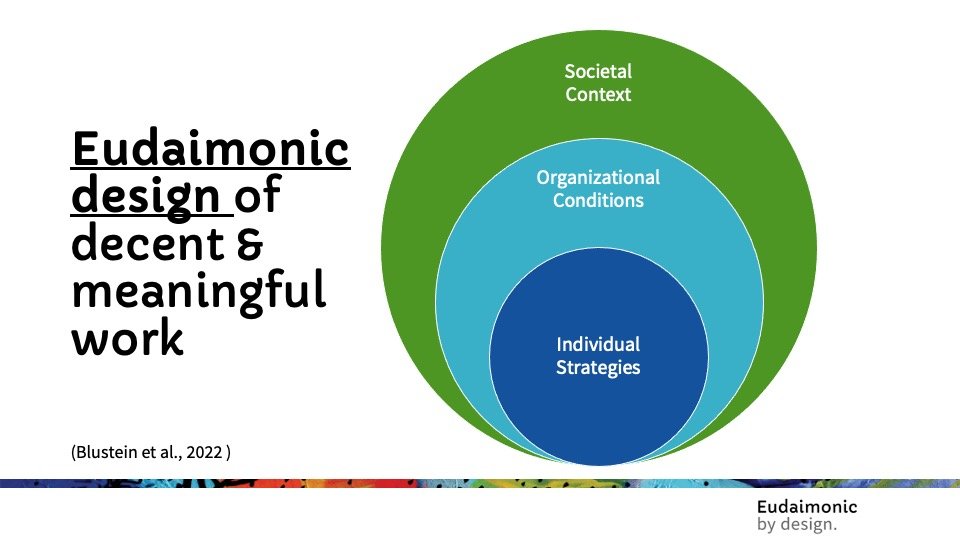

While much of Waterman’s framework focuses on individual awareness and alignment, the conversation closes with a practical discussion about how leaders and organizations can support fulfillment both at work and beyond it.

Not all jobs will be intrinsically motivating, and that’s okay. Every person still has the potential to find meaningful expression somewhere in their life.

Managers can support employees by creating space for strengths exploration, autonomy, and values alignment even if that expression happens outside the workplace.

When employers support the whole person, employees are more likely to feel grounded, satisfied, and capable in their roles.

Soren reflects on how organizations might expand their understanding of growth by including personal development alongside traditional professional development. Together, he and Waterman suggest that fulfillment at work is more likely when people are supported in growing in ways that feel personally meaningful.

Key Ideas to Reflect On

Eudaimonia is about realizing your highest potential by making choices that lead to a lasting sense of fulfillment.

Intrinsic motivation and alignment with personal values are reliable signals that you are on a path toward self-realization.

Work can be experienced as a calling, a job, or something in between. Each orientation has its place, depending on context and individual goals.

When employers support employee fulfillment outside of work, it can lead to greater well-being, motivation, and performance on the job.

Final Thoughts

From Waterman’s point of view, meaningful work is about recognizing your unique strengths, aligning with your values, and having the opportunity to express what matters most to you.

His insights are a reminder that fulfillment comes from choosing what is worth doing and committing to doing it well. This applies just as much to individuals seeking more purpose in their work as it does to leaders responsible for creating environments where people can thrive.

Resources for Further Exploration

Books by Dr. Alan Waterman:

The Best Within Us: Positive Psychological Perspectives on Eudaimonia (American Psychological Association, 2014)

Flow Theory Re-Envisioned: A Conceptual Analysis and Response to Critiques (Oxford University Press, forthcoming Fall 2025)

Related Episodes