In this episode of Meaningful Work Matters, Andrew speaks with Jennifer Tosti-Kharas and Christopher Wong Michaelson, co-authors of Is Your Work Worth It? and The Meaning and Purpose of Work. Jennifer is a management professor at Babson College and an organizational psychologist, while Christopher is a philosopher and professor of business ethics at the University of St. Thomas and NYU Stern.

Together, they bring complementary perspectives to one of the most pressing questions of our time: how do we understand meaningful work, both as individuals and as a society? Their conversation explores why “calling” is a double-edged sword, how 9/11 shaped their research trajectories, and what leaders and organizations must grapple with in a world of “bullshit jobs” and artificial intelligence.

Meaning as Subjective and Objective

Tosti-Kharas approaches meaningful work through psychology, where meaning lives in the mind of the person doing the work. Two people in the same role may experience their jobs entirely differently — one may see it as “just a paycheck” while another feels it is a calling.

Wong Michaelson complements this with a philosophical view. He argues that while work should feel meaningful to us and be valued by society, it must also be meaningful in itself. In other words, people can be wrong about whether their work is meaningful. The example he often cites: the 9/11 terrorists believed their work was meaningful, but their actions were objectively harmful.

Both perspectives highlight a tension that leaders and organizations cannot ignore: meaningful work is both personal and ethical.

The Legacy of 9/11

Tosti-Kharas and Wong Michaelson were management consultants in New York City during the 9/11 attacks. Living through that moment changed not only the course of their lives but also the direction of their research.

They noticed how victims were remembered through their work, and how this collective memory gave work meaning far beyond paychecks or promotions. This became the seed of their first collaborative research project and continues to shape their inquiry into how we ascribe value to work as individuals and as a society.

For many, 9/11 revealed that work is also a way we connect with others, a lens through which we are remembered, and a reflection of what we collectively value.

The Double-Edged Sword of Calling

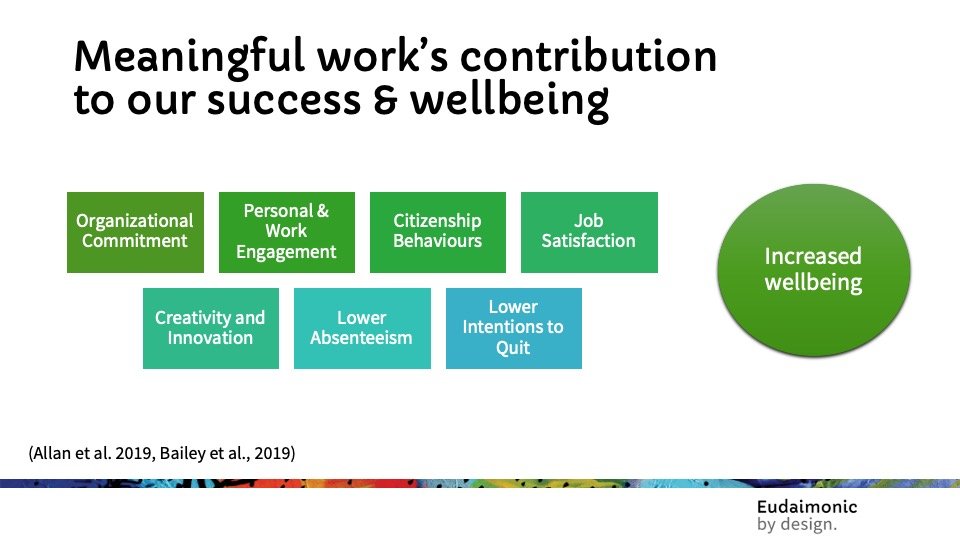

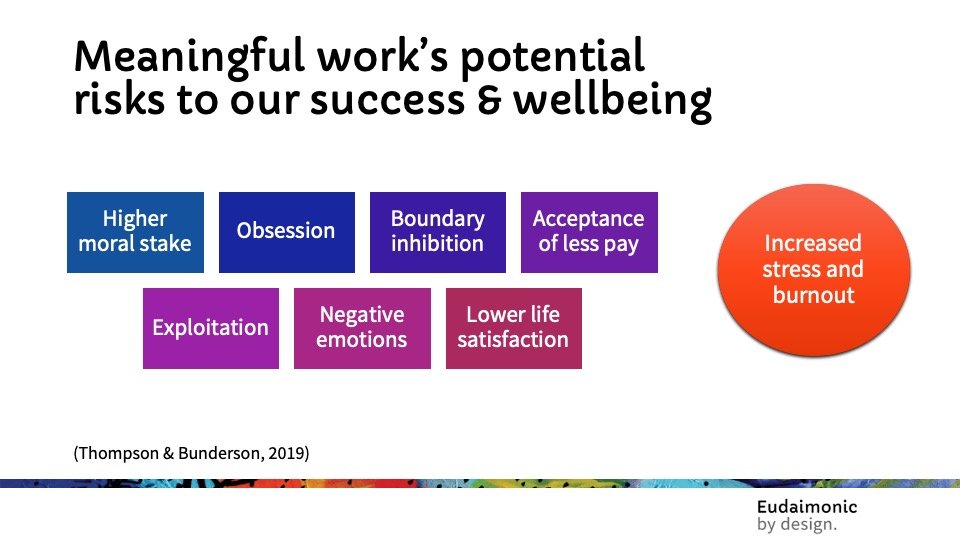

Tosti-Kharas’s research, echoing scholars like Amy Wrzesniewski, shows that seeing work as a “calling” can be powerful, but it can also be risky. Calling can inspire dedication, resilience, and satisfaction. It can also leave people vulnerable to burnout, exploitation, and strained relationships.

In some workplaces, those who sacrifice everything for their jobs are celebrated, while boundaries and balance are overlooked. As Tosti-Kharas notes, “calling” is not available to everyone, and it should not be positioned as the only path to a meaningful life.

For leaders, this means acknowledging both the benefits and the dangers of purpose-driven work.

What Organizations Owe Their People

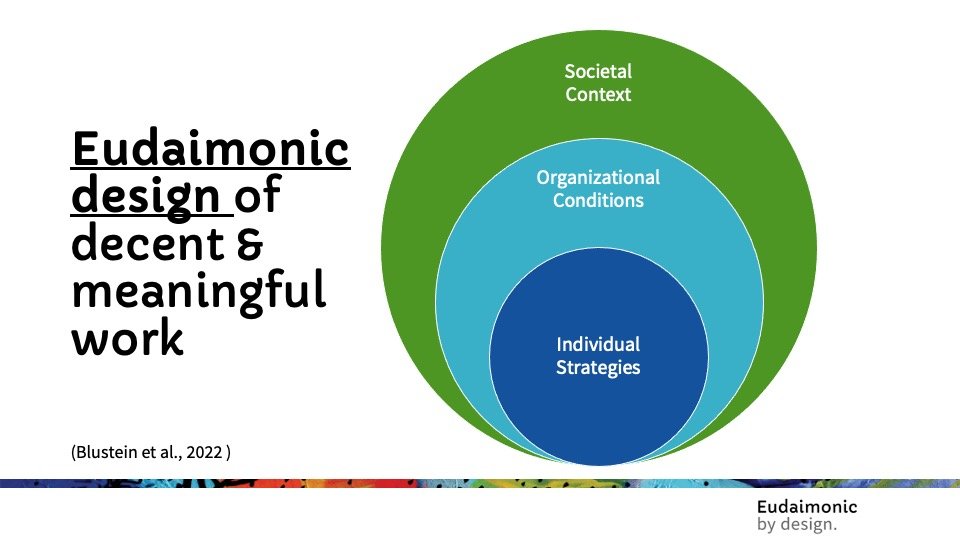

Wong Michaelson’s perspective pushes leaders to ask: What obligations do organizations have when it comes to meaningful work?

It is not enough to craft clever purpose statements or rely on employees’ intrinsic motivation. Organizations must create conditions that respect dignity, promote fairness, and avoid leaning too heavily on employees’ sense of purpose.

Tosti-Khara adds that this responsibility extends beyond knowledge workers.

Nearly half of the U.S. workforce work in jobs that pay less than $20,000 a year. For people in precarious or low-wage jobs, conversations about calling can feel irrelevant or even offensive. Here, meaningfulness may come not from the job itself but from what it enables outside of work — supporting family, giving back to community, or creating stability.

Bullshit Jobs, AI, and the Future

The dialogue also takes on the phenomenon of “bullshit jobs,” as described by David Graeber. Too many people spend their careers doing work that even they secretly believe is pointless. This is damaging to collective well-being, and inefficient.

Looking forward, generative AI raises new questions.

Will it automate the tasks we find meaningless and leave space for work that is truly fulfilling? Or will it strip away jobs that people find essential to their identity? Christopher remains optimistic that uniquely human qualities like creativity and care will continue to set us apart.

But both agree that society must rethink how we define and distribute meaningful work in an era of rapid technological change.

Key Takeaways

Meaning is both personal and ethical. Psychology reminds us that people experience meaning differently, while philosophy reminds us that work should serve a greater good. Together, these lenses expand how we think about what makes work truly matter.

A calling can inspire and harm. Seeing work as a calling can fuel passion and commitment, but research shows it also makes people more vulnerable to burnout, exploitation, and blurred boundaries between work and life.

Organizations shape the conditions for meaning. Beyond slogans or purpose statements, leaders have a responsibility to design jobs and workplaces that respect human dignity, create fairness, and avoid over-relying on employees’ sense of purpose.

The future of work raises new questions. From “bullshit jobs” to the rise of AI, work will continue to evolve in ways that affect how people find and sustain meaning. Being creative, caring, and intentional about how we use these tools will be critical.

Final Thoughts

Tosti-Kharas and Wong Michaelson remind us that meaningful work is never just an individual question. It is also about how we remember one another, what we value as a society, and what organizations owe their people.

As we mark the week of 9/11, their reflections underscore that the meaning of work often becomes most visible in moments of crisis, and that the choices we make about work ripple far beyond ourselves.