In this episode of Meaningful Work Matters, Andrew speaks with Sue der Kinderen, an organizational health psychologist whose work sits at the intersection of work, well-being, and human development. Trained as a counseling psychologist and later earning a PhD in Organizational Psychology, der Kinderen brings both clinical depth and organizational insight to questions of how people experience meaning in their working lives.

In their conversation, der Kinderen and Soren explore eudaimonia at work through a behavioral lens. They look at how meaningful work shows up in what people do every day, how growth, purpose, and relationships shape that experience, and how social context and reflection help sustain meaningful work over time.

Rethinking Eudaimonia at Work

Instead of beginning with how people feel at work, der Kinderen starts with a different question.

What do people do when their work feels meaningful?

From there, she introduces the idea of eudaimonic behavior, describing eudaimonia as something expressed through repeated, everyday actions rather than abstract states or isolated experiences.

Across her research, three patterns appear consistently.

The first is personal growth. This includes behaviors such as seeking learning opportunities, reflecting on experience, and stretching beyond familiar ways of working. Growth, as der Kinderen describes it, unfolds through ongoing engagement with the work over time.

The second pattern is pursuit of purpose. Purpose emerges through alignment. People pay attention to whether what they are doing reflects their values and whether their contribution feels worthwhile within the context they are part of.

The third pattern centers on positive relationship behaviors. Meaningful work develops through interaction, as feedback, validation, and shared reflection shape how people understand their work and their place within it.

Taken together, these behaviors make eudaimonia easier to recognize. They show up in how people engage with their work and how they relate to one another while doing it.

Are These Behaviors Fixed or Changeable?

The conversation then turns to a question leaders often raise: are these behaviors stable, or do they change over time?

Der Kinderen shares findings from her longitudinal research, where she measured eudaimonic behaviors repeatedly over several months.

Some aspects remain relatively stable. People bring tendencies shaped by personality, values, and past experience, and certain patterns tend to show up again and again.

At the same time, context plays a meaningful role. Leadership, work climate, and social environment influence how often people engage in growth, purpose, and relationship-building behaviors.

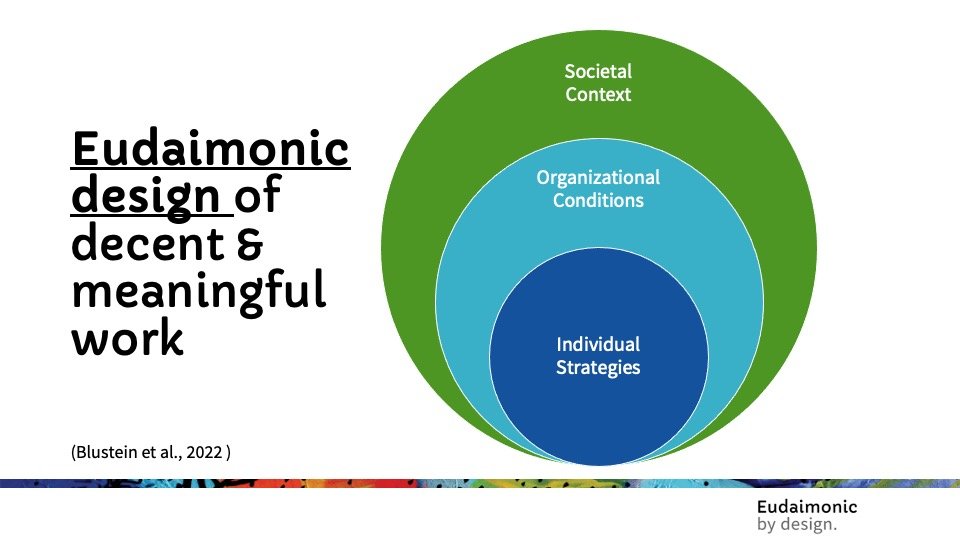

This insight shifts attention beyond individual responsibility toward organizational conditions. Work environments shape whether these behaviors receive support, fade into the background, or never take hold at all.

Why Climate Makes Such a Difference

As der Kinderen explains it, eudaimonic behavior depends heavily on social context. Work climate shapes whether people feel able to engage fully with their work and with one another.

She describes environments where people can speak openly, offer and receive feedback, and show up without fear of repercussion. Civility, respect, and trust create the conditions for honest reflection and growth. This perspective aligns closely with Amy Edmondson’s work on psychological safety, which emphasizes the importance of shared norms that allow people to take interpersonal risks without punishment.

Der Kinderen also notes that meaningful work often includes discomfort. Growth brings uncertainty, values can come into tension, and new roles can stretch familiar identities. In supportive climates, people are more likely to stay engaged through those moments, even when the work feels challenging or unclear.

Reflection as a Necessary Practice

Meaningful questions take time. People need space to pause and consider whether their work aligns with who they are and what they value. Many organizations, however, operate at a pace that leaves little room for reflection.

Soren connects this part of the conversation to a prior Meaningful Work Matters episode with Anu Gorukanti and Laura Holford, whose work through Introspective Spaces focuses on creating moments of introspection in high-pressure environments. In both conversations, reflection supports judgment, care, and sustained engagement.

Der Kinderen describes reflection as something that can be woven into daily work. Coaching conversations, team check-ins, and intentional pauses create space for people to make sense of what they are doing and why it matters.

When Meaning Does Not Come from Work

Der Kinderen also speaks plainly about the limits of work as a source of meaning.

For some people, work plays a primarily transactional role. Others prefer clear boundaries between their work and their sense of identity.

She and Soren talk through what honesty looks like in those situations. Organizations still hold responsibility for fairness, respect, and support, even when the work itself does not feel deeply eudaimonic. People may look for growth, purpose, and connection in other parts of their lives, and that choice does not signal a deficit or failure.

Building Meaning Through Practice

Der Kinderen’s work offers a way of thinking about meaningful work and eudaimonia as a practice. It shows up in how people approach learning, how they align their actions, and how they relate to others over time. Context and climate shape whether those behaviors can take hold and endure, and it unfolds gradually over time.

Resources for Further Exploration

Ncourage | Sue der Kinderen’s platform translating psychological science into workplace practice.

Self-Determination Theory by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber